Adrift

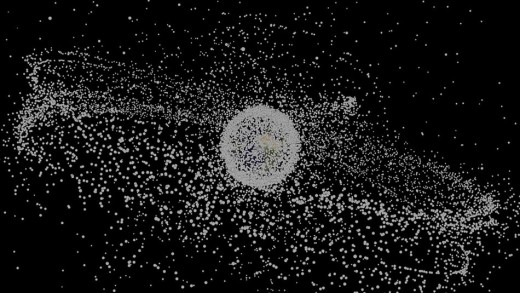

Adrift is a short film that explores the phenomenon of space junk, where human-made objects launched into space and are now defunct orbit the Earth literally as garbage. The film makes visible some of the immediate impacts and dangers of the technological escalation of this culture, where old satellites, spent rocket stages, and other items orbit the Earth, only to collide with one another at high velocities, generating smaller fragments that collide with other items, and so on. The end point is a cascading complex of junk that engulfs the entire space around the Earth. Adrift aims to make this phenomenon visible, putting a big question mark against the claims made by many futurists and technologists that future space colonisation would even be possible, if only it were a tenable or sensible idea in the first place...

Project X is a short film taking viewers on an undercover journey based on formerly top-secret documents that show a partnership between the National Security Agency and telecommunications corporations such as AT&T and Verizon for mass surveillance and bulk data collection of voice and data. The documents reveal TITANPOINTE, the codename for a large windowless sky scraper in New York, where AT&T and other corporations house vast Internet switching equipment and data centres. The facility is also tied to a nearby FBI building, and its rooftop equipment to the SKIDROWE satellite surveillance system. These findings were possible because of documents released to the public by Edward Snowden and other brave whistleblowers.

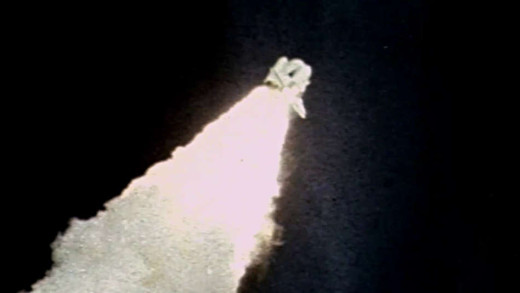

Pax Americana and the Weaponization of Space takes us to the Cold War and beyond, where an arms race of weapons technology plays out by the world's superpowers in space. Satellites, nuclear weapons, tracking technologies, rockets--the weaponisation of space was and is more of the same colonialism in the tradition of empire, much like the sea battles of the 18th and 19th centuries. Indeed, as we learn through Operation Paperclip, the United States recruited than 1,600 scientists from Nazi Germany for work in the Space Race after the end of World War II. Fast forward to today, in the name of protecting commercial investment, the United States has crowned itself with being the so-called "arbiter of peace" in space. But with their weapons industry replacing almost all other manufacturing in America, this claim is ludicrous. More than fifty cents of every US tax dollar is spent on the military. The dream of the original Dr. Strangelove, Wernher von Braun--the Nazi rocket-scientist turned NASA director--has survived every US administration since World War II and is coming to life ever more rapidly. Today, space is largely weaponised, a massive military-industrial-complex thrives, and many nations are manoeuvring for advantage with yet more weapons of war, surveillance, and control.

Spin

Using the 1992 presidential election as his springboard, film-maker Brian Springer captures the behind-the-scenes manoeuvrings of politicians and newscasters in the early 1990s. Pat Robertson banters about "homos," Al Gore learns how to avoid abortion questions, George Bush talks to Larry King about halcyon and other drugs—all presuming they're off-air. Composed of 100% unauthorised satellite footage, Spin is a surreal expose of media-constructed reality, posing larger questions about the functioning of not only corporate media, but the political systems in which they support and how this in-turn plays to the media-constructed reality and so on.

In 1966, Australia made an agreement with the United States that allowed the establishment of a secret military base satellite tracking station, just south of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory. The facility is called Pine Gap and for more than forty years it has operated in a shroud of secrecy and been the target of much controversy. Home on The Range attempts to contextualise these issues by highlighting the history of the base and its origins, as well as the stories of controversy. Some of these include the Khemlani Affair and the sacking of the Whitlam government in 1975, the Christopher Boyce spy trial, the role of the Central Intelligence Agency and its former agent Victor Marchetti, as well as documenting the post-war culture of government secrecy, sprawling intelligence agencies and foreign affairs and policy. But Home on the Range does more than gesture toward such CIA interventions. It marshals a persuasive array of evidence linking the imminent expiry of leases on United States military and intelligence bases in Australia in 1975, to the CIA and Whitlam's sacking, posing direct questions about the nature of democracy in regions beholden to the United States.